SECTION 2:

EQUILIBRIUM

CHAPTER 7 - SOLIDARITY IS A VERB

There is no justice until all of us are free.

Experience, relationships, and power are not limited to what we can see or say. They can be visible, invisible, and hidden, and they play out at both small and large scales within our organizations and society. To adapt a simple definition of racism* to oppression, we could say:

Privilege + Prejudice x Power = Oppression

Solidarity is the ongoing active practice of confronting our own power, privilege and prejudice and supporting others in their struggles.

Oppression is the ongoing unjust treatment or use of authority over others.

Privilege is an advantage or entitlement that benefits members of certain groups above others.

Prejudice is a preconceived feeling or opinion about others.

Change does not happen in a vacuum. We need to support each other’s struggles in order to secure a fairer world. This is solidarity. It is not always easy to confront these challenges and discomforts within ourselves but long-term solidarity is important. This can mean making personal sacrifices, changing our own worldviews and forgoing friends and family in order to do what’s right.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

- Martin Luther King Jr, letter from Alabama jail, 1963

“There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single issue lives” - Audre Lorde

"If you have come here to help me, then you are wasting your time...But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together."

— Aboriginal activist group

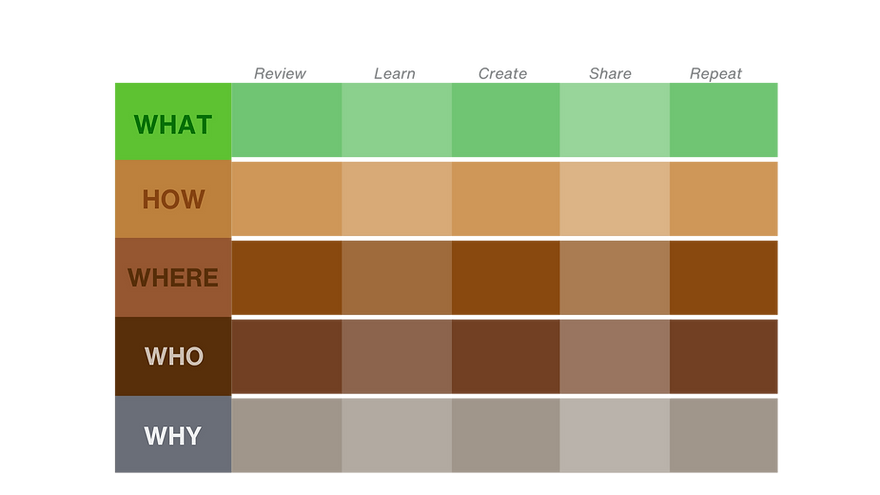

Oppression lives in systems and can affect all of us in different ways at the same time. We have adapted the “Four I’s of oppression”* into five levels to show how oppression works upon us. Trying to challenge oppression at any of its system levels will affect and draw on the others:

-

Internal (What level): What we believe about ourselves, defined by the inequalities, information, structures and beliefs of the dominant system.

-

Inequalities (How level): The system elements, flows and buffers that ensure different life outcomes and income among ourselves - and how they interact and feed back on each other.

-

Interpersonal (Where level): The access to information and relationships that affect how we perceive each other in relation to intersecting identities.

-

Institutional (Who level): The institutions and structures that treat people who hold different identities differently because of racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, and more.

-

Ideological (Why level): The ideas, assumptions and beliefs that shape our understanding of what is right, good, fair, and just.

Just as systems overlap and interact, oppressions can combine, divide and unite people.

Intersectionality, a term created by Professor Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, describes the overlaps between social identities like race, gender, and class, and oppressions like racism, sexism, and homophobia. These take different forms depending on the place or cultural context where someone is. It is important to be aware that this theory was rooted in work Professor Crenshaw did on the experiences of black women in the justice system. Intersectionality as a lens and analytical approach was fundamentally about racism - particularly anti-blackness, overlapping with sexism and classism.

Privilege is any special right or advantage experienced by an individual or group. People with multiple intersecting identities tend to experience multiple kinds of oppression and sometimes privileges ahead of each other, so their perspectives and experiences differ from those who experience fewer oppressions. Simply considering the “most marginalized” groups can be risky because “most marginalized” is often defined by our inability to recognize our own privileges and biases. We need to think beyond our usual limits.

concept: cycle of oppression

The longest-lasting stories based on the stars in the sky result from proactive community collaboration, the desire to find common understanding over many centuries. Collaborating with intent in this way is like applying our own gravity to the world around us.

To achieve the results we want, we need to proactively dismantle oppression to create healthier systems. Problems affect different people in different ways, so we need to work together to find solutions that work for everyone. Working together to tell powerful stories with important messages can positively impact society for many years.

Over the last 100 plus years, most campaign plans in Europe and North America have largely failed to focus on dismantling oppressive systems or making space for the most oppressed to build power. We propose taking a radical approach to power, systems, and solidarity to support others in achieving their goals:

-

Review: Look again at each level of your target system’s star chart to see how oppressions show ideologically, internally, institutionally, and interpersonally.

-

Learn: Educate yourself with the many resources online or offline about oppression and intersectionality. Listen to groups impacted by oppressions perpetuated by the system and observe the key relationships that keep it strong. Really seek to understand this. Do not put burden upon impacted groups by asking them to educate you. Practice continual self-reflection on your own privileges and assumptions. Ask yourself, what is your role in both upholding and dismantling the status quo? How can you do your bit with the privilege you have?

-

Create: Make space for oppressed groups in joint decision-making, in ensuring and reflecting on disaggregated data, and in your messaging. Bring them with you to advocacy meetings with decision-makers. Center their voices to ensure they are heard alongside you, not behind you. This affirms the movement’s equity and starts to shift the harmful norms bound up in the system.

-

Share: Share information, working spaces, funds, volunteers, and other resources.

-

Repeat: Be consistent in delivering on your commitments. Resist recreating an unjust hierarchy in the movement. Solidarity means being prepared to sacrifice your own beliefs for the good of the wider movement if the most oppressed group believes this will best support its cause. Create representative membership of key groups and organizations within your own campaign. Reflect on who makes up the leadership. Be visible, practical, proactive, and committed.

It has been proven that diverse and unexpected movements, where people experiencing different oppressions organize together, can have a huge impact on political decision-making.

Sources: *Read more on the four Is of oppression: https://www.grcc.edu/sites/default/files/docs/diversity/the_four_is_of_oppression.pdf

**Privilege wheel https://unitedwaysem.org/wp-content/uploads/2021-21-Day-Equity-Challenge-Social-Identity-Wheel-FINAL.pdf

story:

breaking barriers: feminist levers & loops in urban mobility transformation bangalore, india, 2019-2023

.png)

tool: social identity wheel

In 2019, traffic and air pollution in Bangalore were major problems. People were stuck in traffic for hours. Due to lack of public transport, private ownership of vehicles was higher than ever. Trees were being cut to build even more road lanes and bridges.

Climate and mobility campaigners urged citizens to pledge to become car-free, and successfully pressured the local authorities to build a 75 km cycle lane. But the public transport system was abysmal, while car-friendly infrastructure meant that people instead spent more on their cars, making the problem worse and leaving the cycle lane hardly used. The campaign had failed to explore the real levers for change.

So Greenpeace India teamed up with allies to dig deeper and find a way to decrease vehicle usage and improve urban mobility. They took the following steps:

-

Learn: Conducted a major audience research exercise among groups of people affected by intersecting systemic exclusions, barriers and oppressions. They found that almost 40% of commuters were women. These women were experiencing multiple, overlapping,forms of oppression severely impacting their safety and agency in the transport system:

-

Interpersonal (Where level): One of the biggest barriers for women commuters in Bangalore was safety - from public transport to cycle lanes they experienced multiple threats from harassment to kidnapping or even worse.

-

Inequalities (What level): When Covid hit, the vast majority of the working-class population could not afford cars and so they had to walk.

-

Institutional (Who levels): Women from working class socio-economic backgrounds did not have cycles or two wheelers, so the time burdens of their daily tasks - from dropping their kids to school, coming back and cooking for the household and then going to their workplaces, like factories - multiplied massively.

-

Ideological (Why level): Cars have always been a status symbol in much of India. But also, in general, city residents felt much safer in private vehicles and so preferred them.

-

Internal (How level): The safety threats, barriers and costs of commuting, and increasing time burdens of work and unpaid care combined to make things very difficult for most women.

-

-

Create: The coalition decided to focus on women commuters as their primary audience. It designed the campaign around their needs and barriers:

-

The coalition asked women from different sectors to join the campaign in planning and advocacy. This included feminist groups, women-led shopkeepers’ associations, transgender movements and several unusual allies joining hands to reclaim and share the city space and affirm their right to commute.

-

Over 200 citizens got together to deliberate on how the city’s budgets should be used and what the mobility system in the city should look like.

-

In Phase 1 the coalition aimed to shift the narrative around the entitlement of the working-class underprivileged women to have access to less costly geared cycles which they could ride wearing saris.

-

In Phase 2 the coalition aimed to make public transport more affordable and accessible, by campaigning for bus lanes that would ensure a faster commute.

-

-

Repeat:

-

A key message was to associate commuting with freedom. This resonated with women especially in the cultural context that the campaign was operating in.

-

The campaign had some big wins:

-

A system-focused approach helped women working class socioeconomic groups to drive and secure system-wide change.

-

The opposition political party made a manifesto commitment to make buses free for women. When this party won the state election, they kept their promise.

-

Daily female passenger numbers rose from 39% to 57%.

-

This big win around mobility and gender increased a sense of agency felt by women across the movement, no matter where they came from.

-

Citizens involved in city level decision making were able to feel part of a collective and garner solidarity for other issues that helped them reclaim their rights and space in the city towards creating more sustainable equitable urban spaces.

The audience-empathetic approach to really understand people’s emotional and psychological barriers helped them to design strategies that shifted the narratives around the city’s mobility. The conversation around gender responsive, safe, mobilities for women and girls has risen in prominence across India. There is no doubt that campaigns like this have played a role in building the critical mass where women are driving conversations around the role of government putting forward policies and resources to address this issue. For example, The Mumbai Development Plan 2034 included a new chapter on gender and inclusion, acknowledging the importance of gender analysis and responsiveness in city planning.

The United Way for South Eastern Michigan’s Social Identity Wheel is an evolving tool to help better map out the different dimensions of our social identities. To quote them: “The wheel allows us to better understand how our identities shape experiences across all dimensions. Social identity refers to the aspects of someone that are formed in relation to the society they belong to. Rather than personality traits or interests that make up your identity and sense of self, social identities describe the socially constructed groups that are present in specific environments within human societies (race/gender/religion, sexual orientation, etc.).”

Try drawing out this wheel and adding the “memberships” or identities that you already claim or that have been ascribed to you, for each identity group.

.png)

tool: privilege walk

This exercise is ideal for a group to do together.

The Privilege walk:

-

Helps each of us consider our own privilege and in relation to each other.

-

Can reveal hidden or invisible advantages that our upbringing, class, race, gender or other identities give to us.

-

Can encourage us to think more deeply about how we might be perceived before, during and after we engage with others in the system.

-

Can therefore inform how we might need to work harder to practice proactive solidarity, collaboration and inclusivity.

Instructions:

-

Have participants form a straight line across the room about an arm’s length apart, leaving enough space in front of the line to move forward 10 steps and enough space behind to move back 10 steps.

-

Read the statements below one by one.

-

When you have read out all the statements below, ask each participant to share one word that captures how they are feeling.

-

Ask the group:

-

Would anyone like to share more about their feelings?

-

Were certain sentences more impactful than others?

-

How did it feel to be one of the people on the “back” side of the line?

-

How did it feel to be one of the people on the “front” side of the line?

-

If anyone was alone on one side, how did that feel?

-

Was anyone always on one side of the line? (If yes: How did that feel?)

-

Did anyone think they had experienced an average amount of privilege, but it turned out to be either more or less than they thought?

-

Did anyone have the thought that their childhood had a deeper impact on their life trajectory than they had previously considered?

-

Statements:

-

If one or both of your parents graduated from university, take one step forward.

-

If you have been divorced or impacted by divorce, take one step backward.

-

If there have been times in your life when you needed to skip a meal or were hungry because there was not enough money to buy food, take one step backward.

-

If you have visible or invisible disabilities, such as difficulty hearing, take one step backward.

-

If your household employs helpers, such as gardeners, cooks, nannies, etc., take one step forward.

-

If you have access to transportation, take one step forward.

-

If you have felt included among your peers at work, take one step forward.

-

If you constantly feel unsafe walking alone at night, take one step backward.

-

If you are able to move through life without fear of sexual assault, take one step forward.

-

If your family ever fled its homeland, take one step backward.

-

If you studied your ancestors and their history in elementary school, take one step forward.

-

If your family has health insurance, take one step forward.

-

If you have been bullied or made fun of based on something you cannot change (such as your gender, ethnicity, physical features, age or sexual orientation), take one step backward.

-

If your work and school holidays coincide with religious or cultural holidays that you celebrate, take one step forward.

-

If you were ever offered a job because of your association with a friend or family member, take one step forward.

-

If you were ever stopped and questioned by the police because they felt you were suspicious, take one step backward.

-

If you or your family ever inherited money or property, take one step forward.

-

If you came from a supportive family environment, take one step forward.

-

If one of your parents was ever laid off, or unemployed not by choice, take one step backward.

-

If you were ever uncomfortable about a joke or statement you overheard related to your race, ethnicity, gender, appearance or sexual orientation, take one step backward.

-

If your ancestors were forced to move to another country, take one step backward.

-

If you would never think twice about calling the police when trouble occurs, take one step forward.

-

If you took out loans for your education, take one step backward.

-

If you and your romantic partner can appear as a couple in public without fear of ridicule or violence, take one step forward.

-

If there was ever substance abuse in your household, take one step backward.

-

If your parents told you that you can be anything you want to be, take one step forward.

This has been adapted from the Kiwanis privilege walk exercise: https://www.kiwanis.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/privilege-walk-2023v6.pdf

There are many iterations of the ‘power walk’ or ‘privilege walk’ which have been used and adapted by feminist and anti-racist educators since at least the 1990s. It is currently unclear who originated the idea, although please do let us know if you know!

.png)

tool: anti-oppression check-list

-

Review: Each level of your target system’s star chart again to explore how oppressions are showing up through ideology, internally, institutions and interpersonally.

-

Learn: Seek out, ask and listen to intersecting groups impacted by the system and key relationships that keep it strong. How are they affected? Really seek to understand this. Check your privileges and assumptions. How can we support these groups?

-

Create: Make space for oppressed groups in joint-decision making, in disaggregated data and in your messaging. Bring them with you to advocacy meetings with decision-makers. Centre their voices to ensure they are heard alongside not behind you. This affirms the movement’s equity.

-

Share: Share information, intel, working space, funds, volunteers and other resources.

-

Repeat: Be consistent in delivering on your commitments. Resist the reproduction of an unjust hierarchy in the movement. Solidarity means being prepared to sacrifice your own beliefs for the good of the wider movement, if the most oppressed group believes this will best support its cause. Create representative membership of key groups and organizations within your own campaign. Be visible, practical, proactive and committed.