SECTION 1: SYSTEM

CHAPTER 2 - THE SIMPLICITY OF

COMPLEXITY

A system’s complexity reveals how far we can shift it.

Systems exist within other systems. If we look closely at an organ inside the human body we see complex systems. If we zoom in, we see cells and atoms. If we zoom out, we see millions of humans living among various structures, organisms and interconnected systems inside communities, towns, cities and countries.

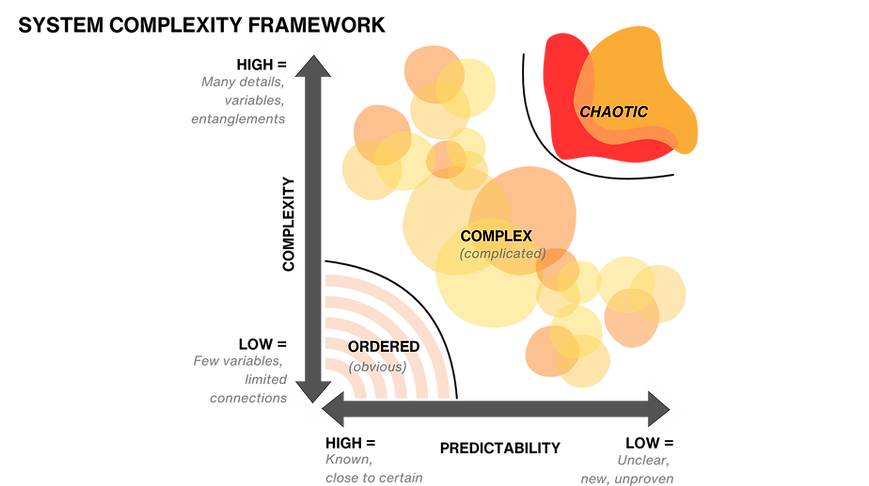

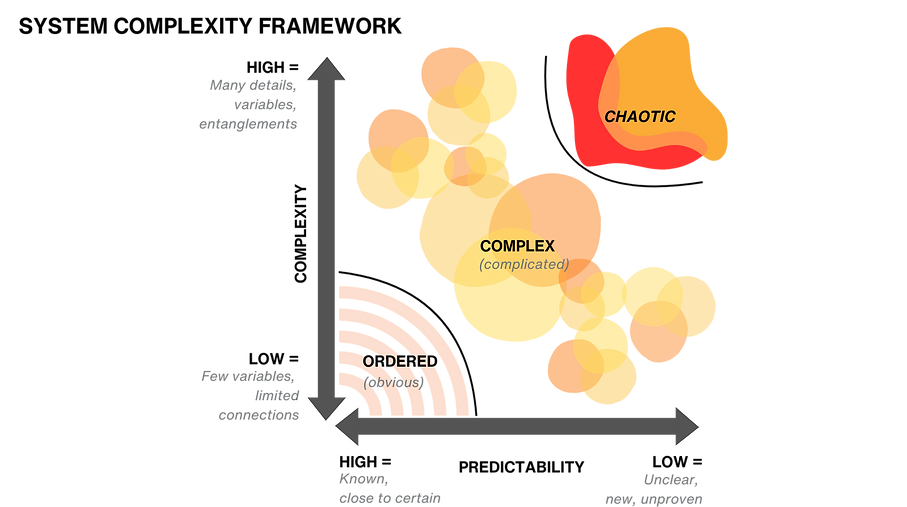

Understanding a system’s complexity is essential before we tackle it. There are three degrees of complexity:

-

Complicated: Predictable and driven by cause-and-effect relationships. Although they have many interconnected parts, their behavior can be predicted if all parts and interactions are understood. For example, a car engine.

-

Complex: Mostly unpredictable and driven by many variables, interactions, and feedback loops. These systems are adaptive and can sometimes be understood in retrospect. For example, the adaptive and self-organizing fungi on the International Space Station.

-

Chaotic: Almost completely unpredictable, driven by numerous variables, dynamic interactions, and loops. These systems are adaptive and inherently uncertain. For example, weather patterns.

Exploring Systems

At any scale, interconnected systems can be ordered / complicated, complex, or chaotic. Consider crossing a river:

-

Complicated System: In a simple ordered system, gravity pulls us into the water, a simple cause and effect. In a Complicated Ordered System, multiple factors like water currents and obstacles affect our steps.

-

Complex System: The river's vibrant life, including fungi, ferns, and fish, adapts and self-organizes.

-

Chaotic System: Including the weather and extended time adds many variables, making predictions difficult.

A common mistake is trying to fix chaotic or complex problems as if they are simple or complicated. This often results in little or no progress. By analyzing and understanding the type of system, we can design a strategy more likely to succeed. For example, when crossing a river, we need to consider gravity, the canoe’s parts, slippery fungi on rocks, and emerging weather conditions. Ignoring these elements can lead to trouble.

Use the complexity tool in this chapter to deepen your understanding of the system you are targeting. We have adapted it from the Stacey Matrix for decision-making and Cynefin framework. By identifying a problem as one of these types, we can start to reveal the kinds of systems, or system interactions, that drive that problem and then identify how to solve the problem.

Once you have used this tool, you could run a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis.**

In 2014, the coal and gas industry planned to expand operations in New South Wales, Australia, but various local communities were opposed to this expansion.

The Gasfield Free Northern Rivers (GFNR) alliance had formed and needed to coordinate a movement that consisted of different autonomous groups working together: farmers, Indigenous people, townsfolk, environmentalists, professionals, and businesspeople. They faced multiple types of challenge: chaotic, complex, complicated and obvious.

The GFNR alliance used the Cynefin framework to assess the best ways to handle these different problems, adapting their strategies and leadership styles. The alliance organized nonviolent direct actions, conducted house-to-house surveys, held public meetings, and used social media to spread their message. They also provided training in nonviolent protest and civil disobedience.

GFNR used the Cynefin framework to experiment with approaches in the following ways:

1. Identified and Adapted to Different Situations: By nudging the system out of chaos into more structured situations through network building and sense-making narratives.

-

Chaotic Situations: GFNR reduced the chaos of the ongoing situation to complexity by supporting new groups to form, new individuals to join existing groups, and by sharing a unifying narrative to make sense of the battle.

-

Complex Situations: The gas industry’s next steps created many unknowns for campaigners. GFNR told the movement there were minimal rules other than “non violent; non negotiable.” This allowed people to organize and adapt quickly through decentralized networks, and come up with new ideas.

-

Ordered (Complicated) Situations: When problems were tricky but understandable, GFNR combined centralized and localized efforts. For example, GFNR sent resident and farmer groups together to advocate to the government.

-

Ordered (Obvious) Situations: When problems were clear and predictable, GFNR knew it could increase pressure quickly via the movement. It used a central database and mobilized all supporters to call the Minister for Resources en-masse.

2. Balanced structure: GFNR used different leadership styles, rotated roles and styles to respond efficiently and effectively at the right times:

-

Distributed Leadership: Different people took on leadership roles as needed. Sometimes leaders took charge, and other times they let others lead.

-

Contextual Flexibility: They changed their leadership and organizational styles depending on the situation, allowing for both centralized and decentralized decision-making.

3. Kept Experimenting to support rapid response and Foster Self-Organization: Enabled creative and adaptive solutions to emerge by applying minimal constraints in complex situations.

-

GFNR continuously tested different approaches to see what worked best. They kept what worked and quickly dropped what did not.

-

Jeff Loy, Assistant Police Commissioner for New South Wales, called the Bentley Blockade, “the largest public order challenge in New South Wales police history.” It took years to build its extensive community support and sophisticated blockade tactics.

-

In the end, the New South Wales government suspended the drilling operation and police operation, and by 2015, the government bought back all gas licenses in the region. The movement successfully protected the Northern Rivers from gas field development.

“… mess is the material from which life and creativity are built …” ― Ralph Stacey

.png)

**Steps for SWOT Analysis:

-

Draw a 2 x 2 table on an A4 sheet or larger.

-

List the strengths and weaknesses of the system you are targeting.

-

Identify opportunities and threats to your success.

Alternatively, analyze the strengths and weaknesses of your campaign and the opportunities and threats for the system or your opponent.

story: the bentley blockade,

australia

.png)

tool: sensemaking

Steps: This tool will help you to unpack the problem and the relationships behind it - to understand the complexity they present individually and together.

-

On an A3 sheet, draw out the Sensemaking chart shown here and write above it a sentence explaining the Problem you wish to change.

-

Relationships: Write out and place a Post-It onto the chart for each key relationship that is maintaining or could help address this problem, according to its level of complexity. These could be tangible or intangible relationships - from the Head of a bank to a local community leader.

-

Connections: Now draw lines between each relationship across the chart. Use thick lines for strong relationships and thin lines for weak ones. Note: You may wish to separate out individuals onto different Post-Its.

-

Complexity: How many influential relationships and competing tensions are there? Might there be other connections among them?

-

Certainty: How predictable are the interactions between these actors and their relationships? Do you need to move the Post-Its around?

-

Sensemaking: Consider the most significant relationships here. Is your problem what you thought it was? Is it Simple, Complicated, Complex, or Chaotic?